RICHARD BERENGARTEN - THE BALKAN COLLECTION

Split, Richard with fellow poet Momčilo Popadić, 19 Feb 1988

This is the first in a set of sketches of former Yugoslav writers by Cambridge poet, Richard Berengarten. Between 1987 and 1990, Richard lived in Yugoslavia. Those three years turned out to be the final ones in that country’s existence. In the following year, aided and abetted by Western powers, the Yugoslav Federation imploded into a series of ethno-nationalistic wars, resulting in the territorial map of the Balkans that we know today. In Richard’s words, “The wars of the 1990s effectively re-Balkanised the Balkans.”

Richard describes his arrival in Yugoslavia in 1987, followed by a short portrait of the poet Tin Ujević, and an English translation of one of his greatest lyrical poems, ‘Daily Lament’. Future issues of The Cambridge Critique will feature several more of Richard’s sketches of writers from what Dubravka Ugrešić calls the Yugozone, including short personal memoirs of novelist Danilo Kiš, of poets Vasko Popa and Desanka Maksimović, and of polymath Eugen Werber, as well as snapshots of other less acclaimed writers who deserve to be better-known to English-speaking readers.

In May 1987, the British Council takes me on as a lector to teach English at the Centre for Learning Foreign Languages in Belgrade. My preliminary contract is to be for one year. Thanks to various short visits since 1982, whether as a poet attending literary festivals or as a lecturer on courses for English language teachers, I’m already familiar with parts of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia.

Before departure, my garage mechanic agrees to help me purchase a reliable car. We find a dealer in London specialising in left-hand-drive vehicles. After taking the train down, at a garage near King’s Cross we see a sturdy second-hand white VW Golf and take it for a spin. On his advice, I buy it on the spot and drive it back to Cambridge. In early July, I let out my house for the year and pack the Golf with basic items I think I’ll need, including a smart new electronic golf-ball Olivetti typewriter, a plentiful supply of ribbons, an electric kettle, an electric toaster, and a second-hand suit that I’ve picked up for £10 from the Salvation Army shop in Mill Road.

I spend the summer in Split as the guest of Daša Marić. I drive to the Dover-Ostend ferry, and from Ostend to Bruxelles. There I set my Golf on the auto-train to Ljubljana, and spend the night in a more-or-less comfortable sleeper. Daša meets me at Ljubljana station the next morning, and we drive down the winding and dramatically beautiful Jadranska magistrala (Adriatic Highway) to Split. We visit the island of Hvar, the coastal towns of Šibenik, Omiš, and Zadar, from which I’ve memories of white-painted buildings with flat roofs where you can sit and sunbathe. Then the ruins of ancient Salona, whose Roman columns lie scattered at all angles in long grass. And then the Ivan Meštrović museum, north of Split. I’ve already seen several of his sculptures at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, and his Caryatids on the summit of Avala, a hill surmounted by a telecommunications tower, ten miles south of Belgrade, as well as what Rebecca West calls a “glorious naked male figure”, perched high on a column Kalemegdan Park, looking out over the river Sava, a statue erected in 1928, celebrating eventual victory over the Ottoman. Actually, I don’t share her enthusiasm for Meštrović’s sculptures, most of which I find craggily crude, bulky and unsubtle. Never mind.

In Split, on the eastern slope of Marjan hill, a promontory overlooking the city and the sea, Daša and I walk around the old Jewish cemetery. We eat seppie in umido (squid in their own ink), which leaves the tongue blackened, a lot of fish, and tender saltmarsh lamb. We also visit an aunt of hers in the small town of Sinj, sheltered among the hills behind Split, to watch the Alka, an ancient lance-spearing contest in which the competitors – burly, moustachioed, costume-clad men – in turn gallop on horseback along a prepared track, as they aim to spear a metal ring suspended on a wire while riding at full tilt, in a ritualised phallic celebration of the warrior-spirit. The alka is the name of the metal ring. This tilters’ tournament takes place annually on the first Sunday in August, to commemorate the victory over the Turkish army in 1715. The tilter who scores the highest number of points (punat) is declared the victor.

In this way, I get a taste of life in Dalmatia, begin to learn a little Serbo-Croat, and acquire at least a basic understanding of the complex interactions and tensions between Croats and Serbs – including the rifts between Catholicism and Orthodoxy, the Roman and Cyrillic scripts, and the cultural influences westward to Rome and north-westward to Venice on the one hand, and eastward to Russia and southward to Greece on the other. I learn a good deal about the history of Yugoslavia, especially of the Communist Party. An uncle of Daša’s was prominent in the movement in the 1920s, when the party was banned and membership an offence punishable by prison. For his pains, he was imprisoned by Tito on Goli Otok (‘Naked Island, Bare Island’) in the 1940s. Daša also introduces me to the poems of Tin Ujević and together we start translating some of them. Later we publish a chapbook containing a dozen of our versions.

Then, very early one morning at the end of August 1987, I set out to drive non-stop through the deep-set valleys of Bosnia and across western Serbia to Belgrade. For some reason I don’t understand, I don’t feel comfortable in these valleys: there’s an eeriness about them, I’ve a sense of claustrophobia, and I take only necessary stops. I manage to arrive the same evening at Branka Panić’s house in the hilly suburb of Voždovac. After staying there for a few days, I rent a small ground floor flat on nearby Gostivarska Street, off Vojvode Stepe. In the spring I’ll hear an unseen nightingale’s songs brilliantly flooding moonlit gardens that are scented by blossoms of a huge variety of tree.

Located on the corner of tree-lined Vase Pelagića and Koste Glavinića in the suburb of Senjak, the Centre for Learning Foreign Languages offers part-time courses. Organised as a co-operative and directed by Branka, this is where I’m to work. From my involvement in events here on several previous short visits, I’ve already made friends among the teachers, including Boba Bobić, who will become the first Serbian translator of my own poems into Serbian.

Augustin (Tin) Ujević is one of the finest Southern Slav lyric poets. This is the first poet I intend to celebrate in this adventure into the past and into some of the poetry of the Balkans. Tin is one of the finest Southern Slav lyric poets of Europe in the first half of the twentieth century.

While his poems are hardly known in English, they’re loved in his native Croatia and throughout former Yugoslavia. I say ‘loved’ advisedly. I don’t mean just admired or respected. At least until the break-up of the Yugoslav Federation, many of Tin’s lyrics were known by heart and quoted by people all over the country, even those who weren’t particularly literary, in much the same way as some of W. B. Yeats’s early poems, like ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’ and ‘Down by the Salley Gardens’, are known and quoted all over Ireland and the UK. This was mainly because people brought up in the various Yugoslav republics learned some of Tin’s poems at school. The sincerity of affection for him as a poet and as a man is apparent even today in South-Slavic countries, especially in the tendency still to refer to him by his pet- name, Tin. And just as the topics of his poems are intimate, and his poetic personality comes across as endearing and sympathetic, so readers in his own language experience and share an intimate response to his poems and feel that they ‘know’ the ‘real’ Tin too.

Born in 1891 in Vrgorac, a small town in the Dalmatian hinterland, Tin grew up in Imotski and Makarska, and attended the classical gymnasium in Split. His language and sensibility are indelibly marked by the rugged beauty of the Dalmatian littoral, that narrow, sunbaked, rocky coastline, backed by mountains, facing out on the Adriatic sea and the islands of Hvar, Brač and Korčula. He spent many years living in Zagreb, as well as periods in Split, Sarajevo, Mostar, and Belgrade. In his youth, his involvement in the Pan-Slav movement to establish a Yugoslav state earned him the disapprobation of the Austro-Hungarian authorities and the close attention of their police. From 1913 to 1919, he lived in exile in Paris (Montparnasse), where he mingled in the same milieu as other radical writers, artists and intellectuals from Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia, as well as such figures as Picasso, Modigliani, Cocteau, Ehrenburg, and d’Annunzio. He was a thorough-going internationalist and never a nationalist – and least of all a Croatian nationalist.

Throughout his life, he lived simply. Well-known as an anarchic bohemian, he was a frequenter of bars and cafés, and always poor. Typical photos show him wearing a battered, ramshackle trilby cocked at a lopsided angle. Affectionate anecdotes about him abound, whether true or apocryphal, like the one I heard about him from poet-friends in Kragujevac, Šumadija, in the Serbian heartland. It goes like this: Tin is sitting in a bar with friends, blindfold, tasting wines from all over Yugoslavia and identifying them. He sips half a dozen samples in turn, swirls each one around his mouth, and names all of them in quick succession without a single mistake. Then someone thrusts a glass of water into his hands. He takes a slurp. “No, I don’t recognise that one,” he says. Other stories aren’t so salubrious. There’s one about him taking off his hat, picking two fleas out of his hair, and inviting his friends to place bets on a race between them across a café table. Apparently, he spent five years in the French Foreign Legion, though I haven’t yet found out when or where he served.

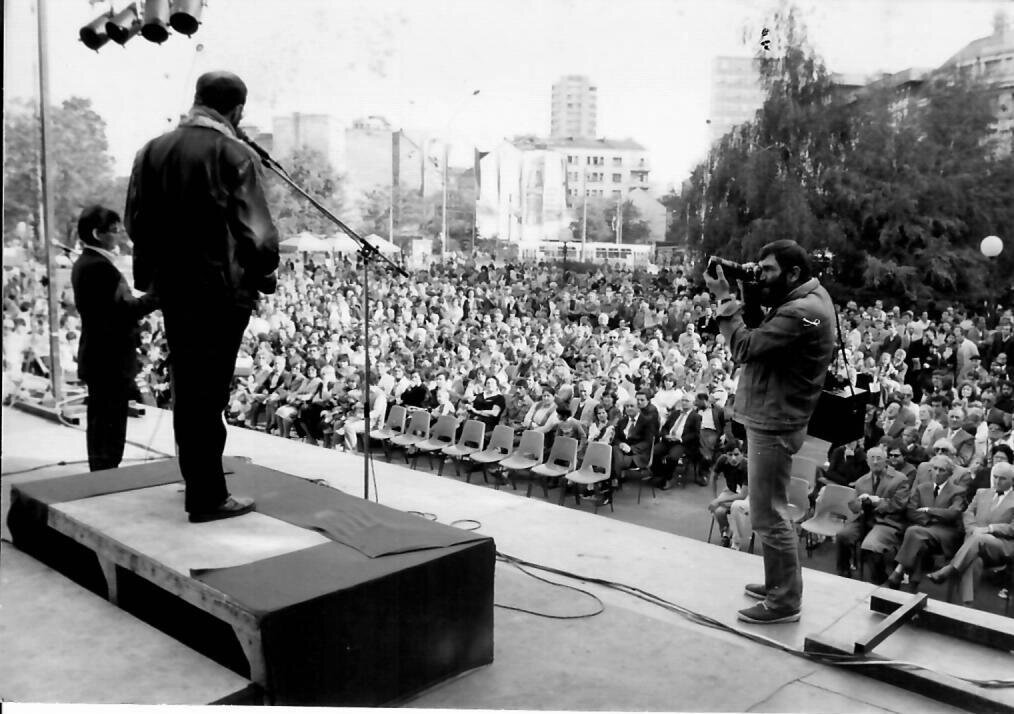

A crowd listens to Richard read his poetry in Belgrade, 1984

The Sava as it flows into the Danube, Belgrade 1987

When I first went to live in former Yugoslavia in 1987, the poems of Tin’s I first came across were his most anthologised pieces. In Split, 1987, Daša Marić asked me to try translating some of these best-known poems, and because my Croatian at that time – or rather, my Serbo-Croat – was a beginner’s, she helped me by making literal versions, which we worked from together. Later, in Belgrade and then in Cambridge, I became more or less proficient enough to translate several more poems alone.

Tin’s art is delicate, highly crafted, akin to that of filigree. Translation of a poet as intricate as he is sometimes works, sometimes doesn’t. You try things out, one after another, you keep your head down, you follow your nose, you fool around, you suddenly wake up in the middle of the night with a better alternative for a phrase running through your head, you turn the light on and scribble it down for fear of forgetting it, you recheck it next morning, you revise, you polish – and sometimes, if you’re lucky, one or two poems do come out right.

Of course, I felt it at all times necessary to transmute Tin’s form, in both the narrow and broad senses. At the micro-level, his patterns of rhyme, rhythm, melopoeia and so on, and at the macro-level, his overall musicality and sense of number, measure and measurement, are integral to his poems and inseparable from their overall meaning – though number and measure of course come in at all other levels too. At any rate, without rendering all these elements, Tin’s genius gets lost. ‘Meaning’ is in no way reducible to ‘literal meaning’.

Although Tin’s major achievement is as a lyricist, his oeuvre is much broader than lyric alone. He was a writer of profound and discerning intellect, broad and capacious interests, inquisitive appetite and eclectic range. His Collected Works number sixteen volumes, including poems in many forms, from free verse to prose-poems, as well as essays, criticism, aphorisms, translations, and a book of thoughts and jottings compiled into a personal ‘encyclopaedia’. The crafted quality of Tin’s lyrics is often flawless and their perfection of musicality is comparable, I think, to that of Verlaine. His most celebrated lyrics are those in the collection Kolajna [The Necklace] (1926). All his poems of the 1920s are immediately approachable in their surface lucidity and simplicity. Every poem is interpretable as a formally composed container or vessel from which an interior feeling emerges. And if it’s a truism that exploration and expression of subjectivity are part and parcel of all lyrical poetry, what particularly characterises Tin is that the feeling itself appears to be allowed ‘out’ and ‘up’ in the very instant of being felt; or, rather, it’s released, simply and clearly, in the precise moment of being apprehended. That is to say, it’s expressed directly, with neither resistance nor hesitation, and certainly with no need of filtration through the kinds of self-irony, emotional reticence or linguistic gamesmanship that mark a good deal of modernist and post-modernist writing. There’s artifice, to be sure, and it’s of a high order: Tin is far too sophisticated a poet ever to be interpretable as a naïf. Once (or, rather, if) this point has been accepted, it then becomes clear that his artifice operates so unobtrusively that it implies an effortless spontaneity and sincerity. At this level of reading, then, if there’s an impression of transparency in Tin’s lyrics, this becomes convincing and genuine thanks to his artifice. Among all the gems in Tin’s ‘necklace’ of poems, it’s fitting, I think, to draw particular attention to ‘Daily Lament’ (‘Svakidašnja jadikovka’). Unrhymed, but with an inescapable, incessant, pounding rhythm, it insists, with slow inevitability, on successive waves of feeling that tumble over one another in rapid succession, oscillating between unease, anxiety, angst, anger, anguish and despair. Here’s a poem that, from the point of view of both subject matter and tone, takes every imaginable risk. It is, in all senses, on the edge. At the same time, in its modulation, pace and emphasis, its patterning is flawless. I don’t believe there is a human being, however sanguine, who hasn’t at some time felt something of what it expresses. And what’s perhaps most astounding about it is the vitality, vigour and dignity that pulse through it. Even in the fulness of its diatribe against life’s pains and difficulties, in its beat, its breath, it’s paradoxically most full of life. This poem is generally agreed to be Tin’s lyrical masterpiece. It’s universally powerful. And it feels strongly relevant to very widespread feelings during the COVID pandemic.

Tin Ujević

DAILY LAMENT

How hard it is not to be strong

how hard it is to be alone,

and to be old, yet to be young!

and to be weak, and powerless,

alone, with no one anywhere,

dissatisfied, and desperate.

And trudge bleak highways endlessly,

and to be trampled in the mud,

with no star shining in the sky.

Without your star of destiny

to play its twinklings on your crib

with rainbows and false prophecies.

– Oh God, oh God, remember all

the glittering fair promises

with which you have afflicted me.

Oh God, oh God, remember all

the great loves, the great victories,

the wreaths of laurel and the gifts.

And know you have a son who walks

the weary valleys of the world

among sharp thorns, and rocks and stones,

through unkindness and unconcern,

with his feet bloodied under him,

and with his heart an open wound.

His bones are full of weariness,

his soul is ill at ease and sad,

and he’s neglected and alone,

and sisterless, and brotherless,

and fatherless, and motherless,

with no one dear, and no close friend,

and he has no-one anywhere

except thorn twigs to pierce his heart

and fire blazing from his palms.

Lonely and utterly alone

under the hemmed in vault of blue,

on dark horizons of high seas.

Who can he tell his troubles to

when no-one’s there to hear his call,

not even brother wanderers?

Oh God, you sear your burning word

too hugely through this narrow throat

and throttle it inside my cry.

And utterance is a burning stake,

though I must yell it out, I must,

or, like a kindled log, burn out.

Just let me be a bonfire on

a hill, just one breath in the fire,

if not a scream hurled from the roofs.

Oh God, let it be over with,

this miserable wandering

under a vault as deaf as stone.

Because I crave a powerful word,

because I crave an answering voice,

someone to love, or holy death.

For bitter is the wormwood wreath

and deadly dark the poison cup,

so burn me, blazing summer noon.

For I am sick of being weak,

and sick of being all alone

(seeing I could be hale and strong)

and seeing that I could be loved),

but I am sick, sickest of all

to be so old, yet still be young!

translated from Croatian

by Richard Berengarten and Daša Marić

From Tin Ujević, Poems, Shearsman Books UK

These sketches are part of Richard’s book Balkan Spaces, forthcoming in 2021 from Shearsman Books.